Where I write from: legacies, inner freedom, and Words of Life

A reader asked me to clarify my background. Below are the spiritual legacies, ethical commitments, and foundational texts that underpin these dialogues, presented without affiliation or mandate.

This article is the author’s own translation of the original French version.

My dear readers,

One of my correspondents recently suggested that I clarify my identity and state where I am writing from, so as not to risk being suspected of insincerity and to remove any ambiguity regarding my commitments as an author.

His remark surprised me at first: I thought that all my writings—here, in these Dialogues of the New World, elsewhere in my Chroniques du Mieux-Être devoted to holistic well-being, or on my artist website jeronath.net—were sufficient to paint a clear picture of my motivations, my loyalties, and my heritage.

However, upon reflection, I understand the reader’s need to quickly situate the writer, especially in an era when what has become commonly referred to as “conflicts of interest” are multiplying, and when everyone, often despite themselves, is looking for simple reference points: a box, a label, a shelf in the mental library. I therefore thank my interlocutor for inviting me to clarify my “position”—if that word still has any meaning when one refuses to reduce one’s inner life to partisan alignment.

Preliminary remarks: no conflicts of interest

I will begin with some preliminary remarks and aim to be as clear as possible. Overall, I have no doctrinal, institutional, or commercial conflicts of interest. As a therapist, I do not represent any brand, certified method, or official school. As a spiritual seeker, I am not an ambassador for any movement, authorized line, or established religion. I am not affiliated with any political party or ideological structure. As an artist, I do not belong to any school, nor do I claim to belong to any defined aesthetic movement.

What characterizes me is a real freedom from the things that usually classify individuals. This does not mean an absence of heritage or a fantasy of self-creation: I know what I owe to encounters, texts, traditions, and influences—and I do not intend to hide these debts. I simply refuse to confuse gratitude with alignment, and filiation with obedience.

Nomadic Jewish heritage: the Name and ethics

Regarding the spiritual aspect—which is the living heart of this publication—I often summarize my heritage in this paragraph, already present on the “About” page:

“A nomadic Jew, brother to all men, a Hasid imbued with all memories, all languages, all signs invented by those who seek the Truth from generation to generation, companion to all those who want to establish the reign of Love, Justice, and Peace here on earth, whether they are believers or not, and who want to end the time of domination and lies, a little Franciscan, a little Sufi, a little Buddhist, a little anarchist, but an anarchist of Love.”

This statement presents me as a “nomadic Jew,” and I indeed claim this formative heritage of the Jewish tradition and its unique spiritual and symbolic significance.

The biblical God has a name, the Tetragrammaton, which, according to tradition, is not pronounced. In reading and prayer, it is replaced by another designation. This substitution is not merely a ritual detail; it signals something essential: a pronounceable name is merely a human construct, a linguistic crutch, and a mental category that cannot fully capture what it designates. It reminds us that the divine cannot be confined to our concepts and that any theology, when it claims to conclude, risks betraying what it believes it serves.

In the Jewish tradition, the primary concern is not to impose a doctrine, but rather to embody an ethical imperative. A famous passage from Deuteronomy expresses this idea with radical sobriety: “This commandment that I prescribe to you today is not extraordinary; it is not far away. It is very near you; the Word is in your mouth and in your heart to fulfill it. See, I have set before you today Life and Good, death and evil.” Further on, it says: “I call heaven and earth to witness against you today: I have set before you Life and death, blessing and curse. Choose Life, so that you and your descendants may live.”

These words are addressed to a people in transition: the Hebrews in the desert, who had left Egypt—that matrix of social and spiritual strangulation—and were walking toward the Promised Land, whose image concentrates a symbolism of remarkable density. We see humanity in the process of transformation: slow, contested, vulnerable, but called to become capable of a more just society. The emphasis is not on the obligation to “believe rightly,” but on the freedom to choose—and on the responsibility to answer for the consequences, including the collective consequences, of that choice.

I fully identify with this dynamic of constantly questioning sacred writings — not to dissolve their power, but to preserve their purpose. I view them as inquiries about our freedom and our ability to take on human responsibility rather than as definitive answers. All too often, humans have tried to reduce the Words of Life to fixed dogmas—metaphysical slogans that one must adhere to in order to guarantee hypothetical salvation after death.

However, at its core, Jewish tradition speaks first and foremost of a life to be lived here and now—on a land of which we are the prudent and grateful beneficiaries, in a society to which we are accountable, and in a freedom that honors the creature called to participate in a creation whose mysteries are beyond its comprehension.

Brotherhood: openness, protection, hope

The above statement goes on to specify that I consider myself the “brother of all human beings.” This disposition does not require any common affiliation—be it religion, “race,” nation, political party, opinion, or social class—nor any other determining factor that would obligate me to exclude part of humanity from my circle of consideration. This attitude is unconditional and a primary choice that translates into complete openness to encounter, sharing, and discussion.

However, this openness is not naivety. It presupposes, at the very least, that the other person will behave respectfully, — that they will not seek to eliminate me, intimidate me, deny my right to exist, or eradicate part of humanity. When I encounter such a desire for domination or destruction, the other person remains my brother in principle, but I must protect myself and distance myself from them: my brotherhood can no longer be actively exercised in close proximity, even if it remains internally as a fundamental orientation.

For me, this is where a fine line is drawn: maintaining brotherhood without sacrificing integrity and rejecting hatred without consenting to domination. If I withdraw, it is not a definitive condemnation. Rather, it is accompanied by a willingness to forgive and a hopeful expectation of change—not as an excuse granted in advance, but as fidelity to the idea that no one is reduced to their worst actions and that humans are capable of turning back to life.

Being a Hasid: attachment, joy, sanctification

As I wrote in the above passage, I am a “Hasid imbued with all the memories, all the languages, and all the signs invented by those who seek the Truth from generation to generation.” In the Hasidism that emerged in the 18th century around the Baal Shem Tov, a Hasid is, in the deepest sense, a man of attachment. He seeks to remain connected to God (devekut) at the heart of ordinary life. He makes prayer, joy, and trust a way of inhabiting every moment.

For a Hasid, his entire existence becomes glorification, from the simplest material acts—eating, working, and sleeping—to loving one’s neighbor, studying, and spiritual inquiry. The orientation of the heart is as important as scholarship. Everything can become sanctification, gratitude, and remembrance. This is not an escape from the world but a way of passing through it without losing sight of what is essential.

I humbly strive to be that Hasid, seeking to improve every day, to reach my best, and to become as worthy as possible of having been created “in the image and likeness” of God, as Genesis says. Not out of perfectionism, but out of response—responding to the call of Life, the responsibility of conscience, and the possibility of loving more, lying less, and serving better.

Everything that touches the long chain of humans—men and women—who have sought to return to Truth and Goodness since the dawn of time touches and concerns me. Their memories and legacies; the words with which they expressed their hopes and quests; and the symbols that structured their inner lives—every fragment of these riches is a treasure. I receive them as nourishment, as seeds, and sometimes as luminous wounds. When I discover them, they resonate within me as if an ancient part of my being recognizes a word already sensed.

I have always had long, silent conversations with some of them. They are among my greatest debts and most moving expressions of gratitude. This is why I am the “companion to all those who want to establish the reign of Love, Justice, and Peace here on earth, whether they are believers or not.”

Towards a society free from domination

Finally, I am deeply convinced that it is possible to put an end to “the time of domination and lies” and to transform our societies profoundly so that everyone can live in true freedom and fulfill their innermost essence.

It seems to me that each person is the repository of spiritual gifts, unique abilities and riches, as well as a unique life mission; and it is their responsibility to develop and fulfill them, for their own joy, balance, and happiness—but also as a contribution to humanity as a whole, as a gift to the common good.

However, I believe that this metamorphosis can only happen on one condition: that a growing number of human beings agree to actively engage in such a process, remaining open-minded, without clinging to doctrine, and without trying to impose their path on others. It is at this price—and perhaps only at this price—that a new society will become viable: a society of sharing, cooperation, co-responsibility, and co-decision, where we will learn to make room for plurality without renouncing high standards, and for freedom without sinking into indifference.

Influences: Francis of Assisi, Sufism, anarchism of Love

Now, I would like to say a few words about the last part of the above quote: “A little Franciscan, a little Sufi, a little Buddhist, a little anarchist—but an anarchist of Love.” These words sum up many of the encounters, texts, traditions, and influences that have enriched—and sometimes saved—my journey, even if certain experiences are not included.

When I was seventeen, the Poor Clare sisters of a small monastery rescued me from a period of extreme poverty and loneliness. They introduced me to Francis of Assisi and housed and fed me in their guesthouse for several weeks. Even today, I vividly remember their psalms, their songs, and the gentleness of Sister Monique, who welcomed me. I sometimes think back on it with emotion that moves me to tears.

Francis of Assisi’s figure, his love for all beings, his Canticle of the Creatures, and his oft-repeated prayer—”Lord, make me an instrument of your peace; where there is hatred, let me sow love”—accompany and uplift me when the darkness of the world seems too heavy to bear. However, let me be clear: I have not adopted the idea of redemption from sin through Jesus Christ incarnate. I believe, perhaps more radically, that it is not up to God to “make me” an instrument of peace but rather up to me to become one through conscious improvement, patience, and inner rectification.

Later, I recognized in Sufism—both in reading Rumi and in my familiarity with some of his teachings—a particularly accurate, lively, and internal expression of the spiritual momentum carried by Muslim revelation, far removed from the strict caricatures and murderous excesses of radical Islamism. I am not unaware, however, of the difficulties posed by the founding text itself: like many ancient writings, it contains layers, tensions, and passages that are difficult, sometimes contradictory, requiring demanding hermeneutics, careful contextualization, and ethical maturity; without this, certain fragments can be exploited by minds in search of aggressive identity, revenge, or domination. But this is a whole subject in itself, which would require specific and more extensive treatment.

As for the anarchist movement, if I call myself an “anarchist,” it is in the sense of an anarchism of Love. I believe that the time of leaders—in the sense of vertical, sacralized, and irresponsible domination—should be considered over. Human history too often bears witness to immense massacres driven by systems of power in which a few exploit fear, fragility, and the need for consolation, and in exchange obtain the renunciation of freedom by others—that is, ultimately, the possibility of deploying their own human riches.

But I believe just as strongly that a free society will never arise from violence, civil war, or chaos. It can only arise from patience and perseverance: from human groups of a manageable size, brought together in communities where dialogue becomes possible, where co-decision-making is truly feasible, and where brotherly love is not a vague sentiment but a force for social cohesion, an art of relationship, a discipline of listening, and a fidelity to the dignity of each individual.

My “Words of Life”: foundational readings

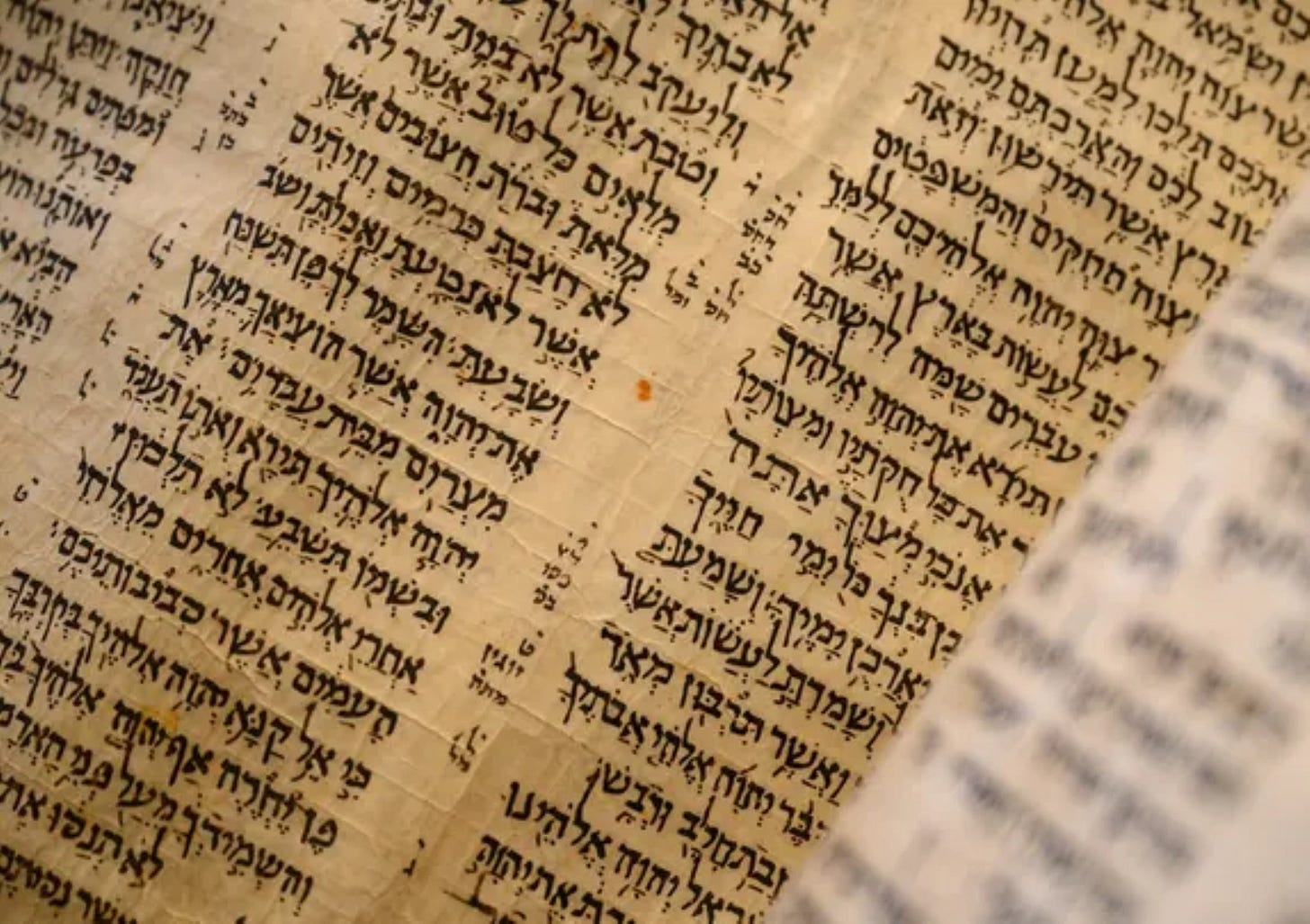

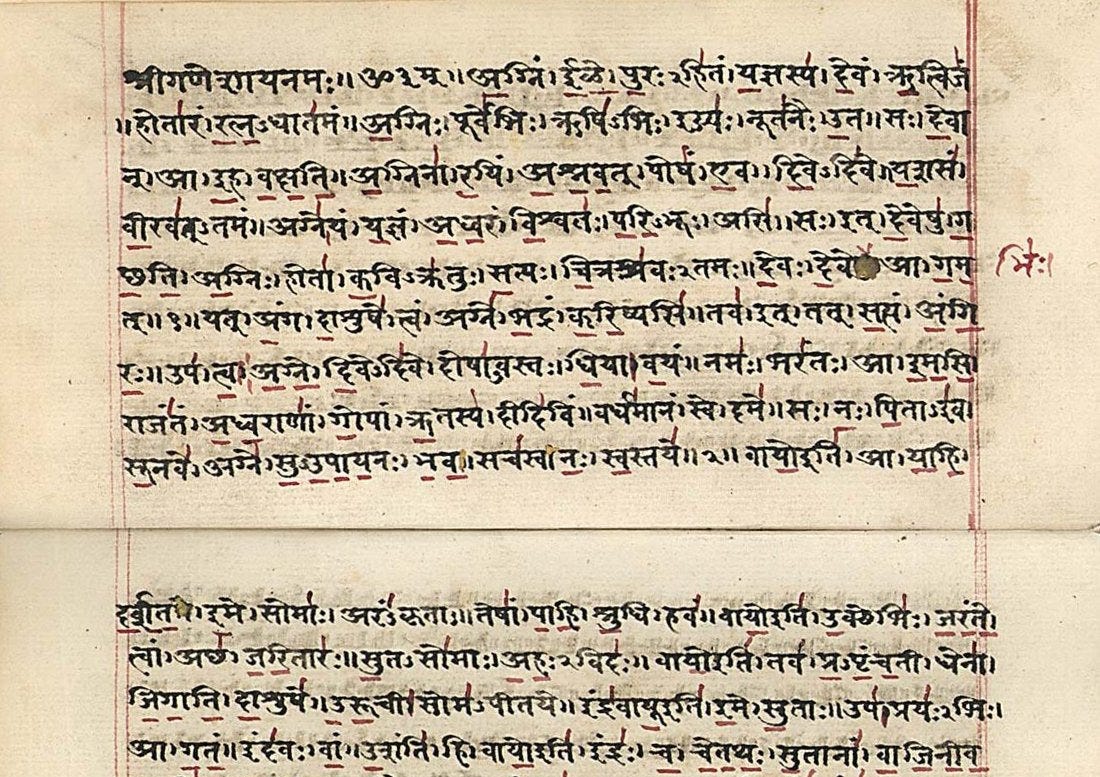

Finally, I would like to say a few words about my foundational readings, which I call my “Words of Life.” As you may have gathered, my study of the Torah remains central to my approach. I am fortunate to read it in Hebrew, which allows me to perceive its richness and layers of meaning that translations cannot convey.

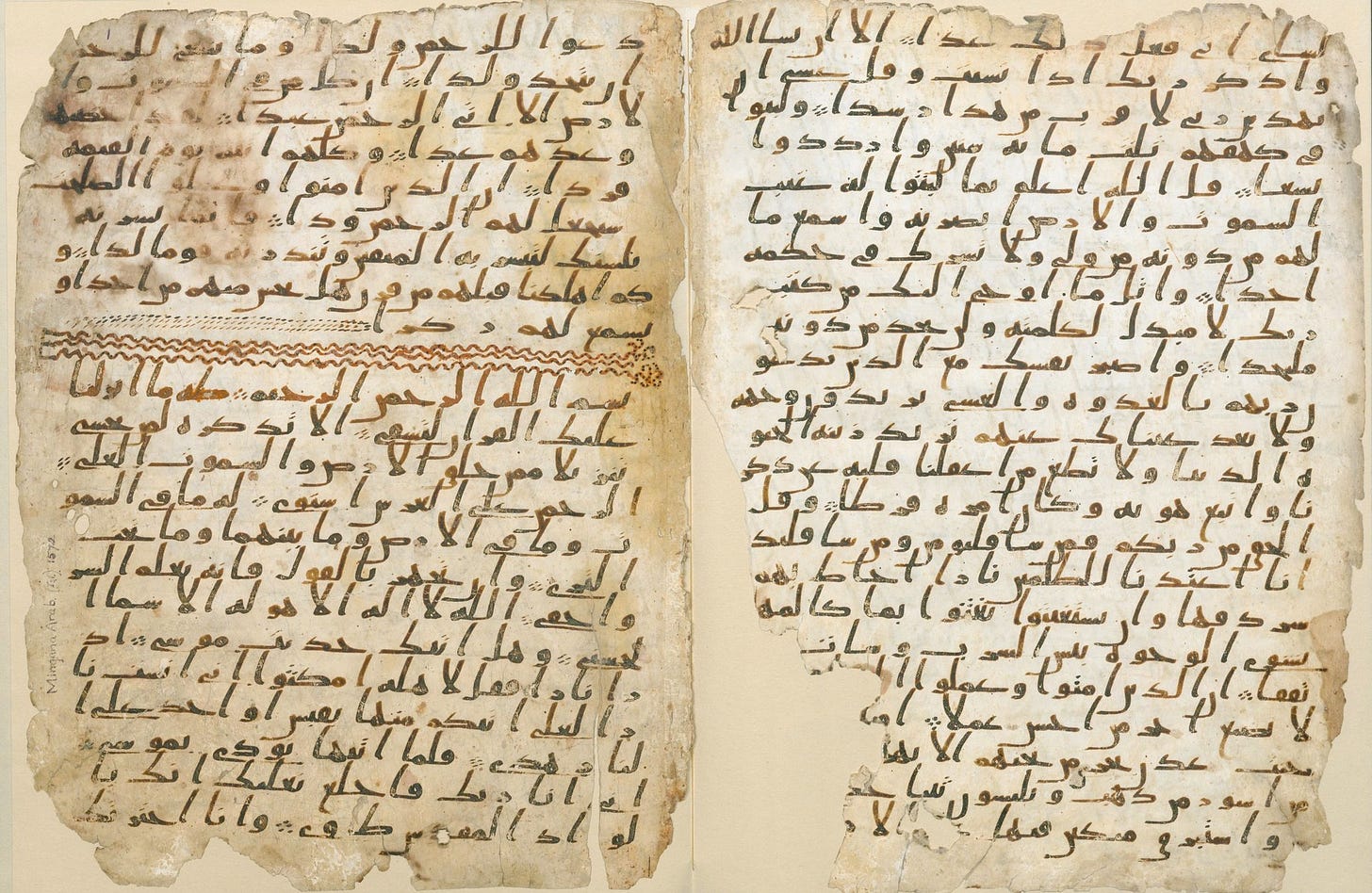

However, it is not the only one. I also read the Quran, unfortunately through translations. I own several translations and use websites, lexicons, and books to shed light on passages that intrigue me. I also draw on the work of Muslim thinkers whose contextualization and interpretation of the text allows for a more accurate understanding.

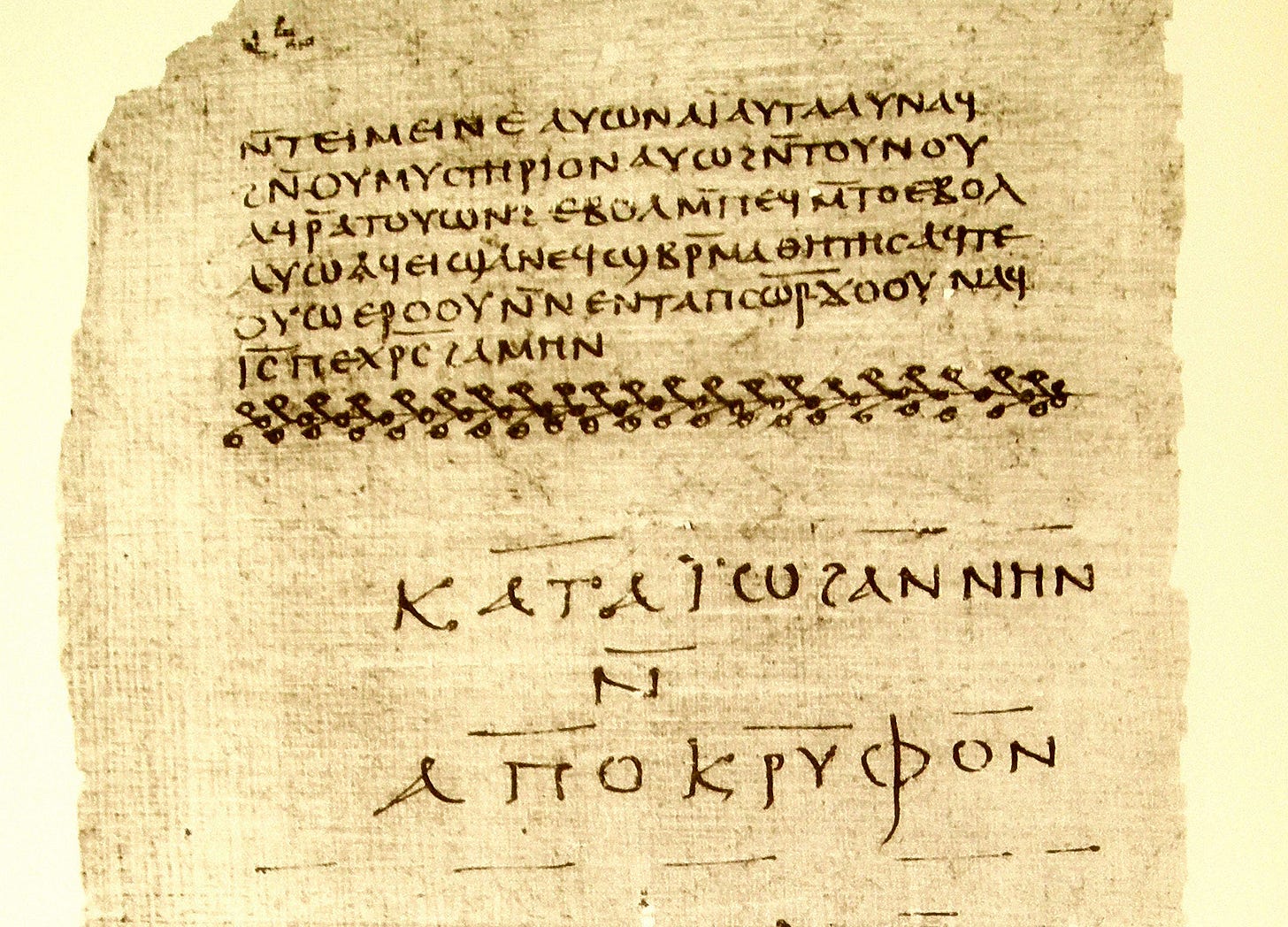

The Gospels—both canonical and certain apocryphal ones, such as the Gospel of Thomas—are also among my sources of reflection. Depending on the period, I also read translations of the Peshitta and the Hebrew version of the Gospel of Matthew. This version was preserved in certain Jewish circles that had to defend themselves against Christian accusations in theological discussions over the centuries. This climate is attested to by the Barcelona Disputation, as reported by Nahmanides.

In the East, I began studying Sanskrit in my early years under the formative influence of René Daumal, an author enamored with the absolute who, at the end of his short life, was a student of Gurdjieff. Life’s twists and turns forced me to abandon this study, but I never stopped reading and working on the great texts of Hinduism—the Vedas, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Upanishads—nor did I lose interest in the tradition as a whole, including its musical culture, which has fascinated me for a long time.

I also discovered Zen Buddhism and Theravāda Buddhism at a very young age—often presented as one of the closest, in terms of its sources, to the ancient teachings of Buddha. I was introduced to their meditative practices, and over the years, other forms of meditation naturally became part of this foundation. I regularly read the Pāli canon, as well as works from these two traditions.

Similarly, part of my life has been devoted to the study of Taoism. I have immersed myself in the Tao Te Ching as well as the texts of Lie Tzu and Chuang Tzu—to name but two pillars—whose paradoxical sobriety and sharp insight still offer a valuable counterbalance to our mental rigidity.

Regarding more recent spiritual influences, I consider two works to be of great importance: Dialogues with the Angel, transmitted by Gitta Mallasz, and Revelation of Arès, sometimes called “The Sign,” transmitted by Michel Potay. The first invites us to deeply reconsider our relationships with ourselves, the invisible, and how we act and conduct ourselves in human affairs. The second, while continuing in the Abrahamic tradition, seems to me to offer a powerful lever to free us from certain superstitions—both religious and political—and place us in a dynamic of personal transformation, inseparable from an active effort to re-spiritualize our era.

I realize how bold such a statement may be, but I make it with conviction: If humanity does not close itself off, if it does not betray the spirit in favor of labels, then this text, the Revelation of Arès, could be recognized in a few decades or centuries as one of those books that permanently shift consciousness and ethics. It would be on par with the great Scriptures that have structured our history. I sincerely hope it will not lead to a retreat into identity politics or close-mindedness, which would negate precisely what is rebellious and innovative about it.

Closing remarks: invitation to dialogue

There you have it: I believe I have responded faithfully and honestly—as much as is possible in a text that was not intended to be lengthy or autobiographical—to my correspondent’s invitation. I hope that these few clarifications will enable each of my readers to better understand the author who expresses himself here, in these Dialogues, and who invites them to exchange with him on human destinies, spiritual life, and what we do, together, with our share of responsibility for the future.

January 14, 2026,

Jérôme Nathanaël

© 2026 - Dialogues of the New World by Jérôme Nathanaël

The distinction you make between gratitude and alignment is super sharp. I've noticed that tension myself when people expect spiritual commitment to mean institutional loyalty, but the Hasidic approach to devekut as you describe it sidesteps that whole trap. The part about "Words of Life" being a living inquiry rather than dogma rang true, especially since i've seen how fixation on doctrine can freeze what should be dynamic ethical engagement. Interesting how the Revelation of Arès reference positions this alongside older traditions without claiming to replce them.