Reading the Words of Life: toward an hermeneutics of freedom

Breaking free from conditioning, honoring the plurality of meanings, dwelling in silence: a path for foundational texts to truly encounter us.

This article is the author’s own translation of the original French version.

Introduction: the contemporary reader’s malaise

We live in an era saturated with texts. Never before has humanity had such immediate and massive access to writings from all times and all traditions. Yet never, perhaps, has it been so incapable of truly reading—that is, of encountering a text in the depth of what it has to say, without immediately reducing it to what we want to find in it.

This difficulty reaches its paroxysm when it comes to what I call the Words of Life: those foundational ancient writings—Torah, Qur’an, Gospels, Vedas, Tao Te Ching, Pali Canon, but also recent ones—Revelation of Arès, Dialogues with the Angel—which carry within them a word that aspires to transform the one who approaches them. For these texts don’t merely transmit information; they interrogate our existence, they call us to transform ourselves, they place us before ethical and spiritual choices that engage our entire life.

Yet, precisely because they touch the most intimate part of ourselves, we almost never truly read them. We believe we’re reading the Torah, the Qur’an, or the Gospels, when in fact we’re merely projecting onto them our familial conditionings, our inherited fears, our beliefs imposed since childhood, our undigested revolts, our needs for security or rebellion. Each reading then becomes a mechanical reading, governed by unconscious automatisms, fragmented by the plurality of contradictory “I’s” that succeed one another in us without coherence. And the text, instead of interrogating us, transforms itself into a simple mirror of our projections—a mirror that reassures or frightens us, but never truly encounters us.

How do we escape this impasse? How do we learn to read truly, so that the text can unfold its own word without being immediately domesticated by our conditionings? How do we avoid the twin pitfalls—the naïveté that accepts everything without critical distance, and the cynicism that rejects everything while claiming to demystify? How do we practice a free reading, neither submitted to the external authority of an institution or dogma, nor delivered to the relativism that dissolves all meaning?

These are the questions I would like to try to answer here, drawing on the hermeneutical treasures of several traditions—Paul Ricœur’s philosophical hermeneutics, Talmudic hermeneutics as deployed by Marc-Alain Ouaknin, and the teachings of Krishnamurti and Gurdjieff on consciousness and conditioning. Together, these approaches outline the contours of a hermeneutics of freedom: a way of reading that honestly recognizes our limitations, refuses all dogmatic closure of meaning, and places itself in the service of a real transformation of being.

I. Recognizing conditioning: where I come to the text from

The invisible threshold: we never arrive alone

Before even opening a sacred text, I must recognize an uncomfortable truth: I never arrive alone to reading. I am accompanied by silent generations, by unavowed prohibitions, by undigested hopes, by sedimented collective wounds. My reading is never virgin; it arrives loaded with religious or anti-religious heredity, with words heard in childhood, with inherited fears, with hopes transmitted through imitation.

Krishnamurti starts from an implacable diagnosis: the human being is integrally conditioned. This conditioning is not partial—some “bad habits” that could be corrected by an effort of will. It is total, and touches all dimensions of our existence: our biology (instincts, bodily reactions), our family history (parental models, inherited traumas), our culture (language, values, norms), our religion (imposed beliefs, images of God, fears of sin), our ideologies (political systems, class belongings, national identities).

As Krishnamurti affirms: “The mind is therefore conditioned in its entirety; there is no part of the mind that is not conditioned.” This means there exists no “free zone” from which one could objectively observe other conditionings. We are entirely caught in the net.

The plurality of “I’s”: who is reading at this instant?

Gurdjieff introduces a psychology radically different from classical psychology: “This ‘I’ does not exist, or rather there are hundreds, thousands of little ‘I’s’ in each of us.” We believe we are “one.” We say “I think,” “I want,” “I believe.” But this unity is an illusion. In reality, we are a chaotic multiplicity of contradictory “I’s” that succeed one another without coherence: the intellectual “I” that reads a philosophical text, the emotional “I” that seeks consolation in a psalm, the fearful “I” that seeks security in a dogma, the rebellious “I” that rejects all religious authority, the sentimental “I” that is moved by a prayer, the cynical “I” that demystifies everything.

These “I’s” don’t know each other. Each pretends to be “I,” each pretends to speak in the name of the person’s totality. But in reality, they succeed one another mechanically, governed by automatic associations, habits, conditioned reactions.

This fragmentation has direct hermeneutical consequences: depending on which “I” dominates at the moment of reading, the same text will be understood differently. Monday morning, dominated by the “intellectual I,” I read a verse as an abstract ethical principle. Tuesday evening, after a dispute, dominated by the “wounded emotional I,” I interpret it as a condemnation of those who hurt me. Wednesday, in a depressive state, I understand it as a personal reproach. Thursday, after a calming meditation, it becomes a call to spiritual transformation. None of these “I’s” remember what the other understood. Each believes its reading is “the true one.”

The three disconnected brains

Gurdjieff specifies this fragmentation by distinguishing three “centers” or “brains”: the intellectual center (thought, analysis, logic), the emotional center (feelings, desires, affective attractions and repulsions), and the motor center (the body, physical habits, rituals, automatic gestures). In the ordinary person, these three centers function in a disconnected manner.

When I read a sacred text, my intellectual center can understand the literal meaning, analyze the structure, spot contradictions. My emotional center can be moved, overwhelmed, inspired—or on the contrary frightened, revolted. My motor center can mechanically repeat ritual gestures (crossing oneself, prostrating) without intelligence or emotion truly participating. This disconnection produces partial and distorted readings: I can “understand” an teaching intellectually without feeling it emotionally, and thus without it transforming my life. Or I can be moved without understanding, and fall into sentimentalism. Or I can practice a motor ritual without either intellectual or emotional engagement.

Concrete examples: how conditioning filters reading

A Jew reads the Torah. But is it his Orthodox grandfather reading in him? Is it the Shoah filtering his understanding? Is it the rebellion against family traditionalism already structuring his hermeneutics?

A Christian woman reads the Gospel. But is it the fear of original sin imposed by her mother that orients her reading? Is it her conscious feminism that makes her waver on certain Pauline verses?

A Muslim reads the Qur’an. But does he carry his father’s Arab nationalism, the fear of infidels taught by the mosque, or the sincere desire for social justice?

In all these cases, the authority of the text becomes a pretext to legitimize what the conditioning has already decided. It’s not a morally “bad reading”; it’s a mechanical reading, governed by invisible automatisms.

The preliminary task: to observe without judging

Faced with this diagnosis, two attitudes are possible—and both are traps. The first consists of denying the conditioning, pretending one can “read objectively” or “simply follow what the text says.” This naïveté is a form of blindness. The second consists of despairing: “If I’m entirely conditioned, how could I ever truly read?” This despair is a form of resignation.

Krishnamurti proposes a different path: observation without the observer. Normally, when we “observe” something (in us or outside us), there is an observer (the “I” that looks), an observed (what is looked at), and a distance between the two. This distance immediately creates a duality: the observer judges, compares, evaluates, rejects or accepts what it observes. And this observer itself is the product of conditioning.

Observation without the observer consists of observing conditioning without judgment, without seeking to suppress it, correct it, flee it. Of seeing how the observer itself (the “I” that claims to observe) is part of the observed conditioning. Of remaining in this observation without seeking a solution, without wanting to transform what is seen. Krishnamurti affirms that if the observation is total, the conditioning dissolves by itself. Not by will, not by effort, but by the simple clarity of vision.

Gurdjieff, for his part, proposes self-remembering: being present simultaneously to oneself and to what one is doing. It’s a state where I see what I’m doing (for example, reading a text), I see myself doing it, I see which “I” dominates at this moment, I see how my intellectual, emotional or motor center reacts. This self-consciousness is not natural. It comes in flashes, briefly, then disappears. But when it’s present, it creates a space of freedom: I’m no longer identified with my reaction, so I can see it for what it is (a conditioned mechanical reaction), and let the text resonate differently.

II. Deconstructing historical layers: the specific problem of ancient texts

The hermeneutical palimpsest

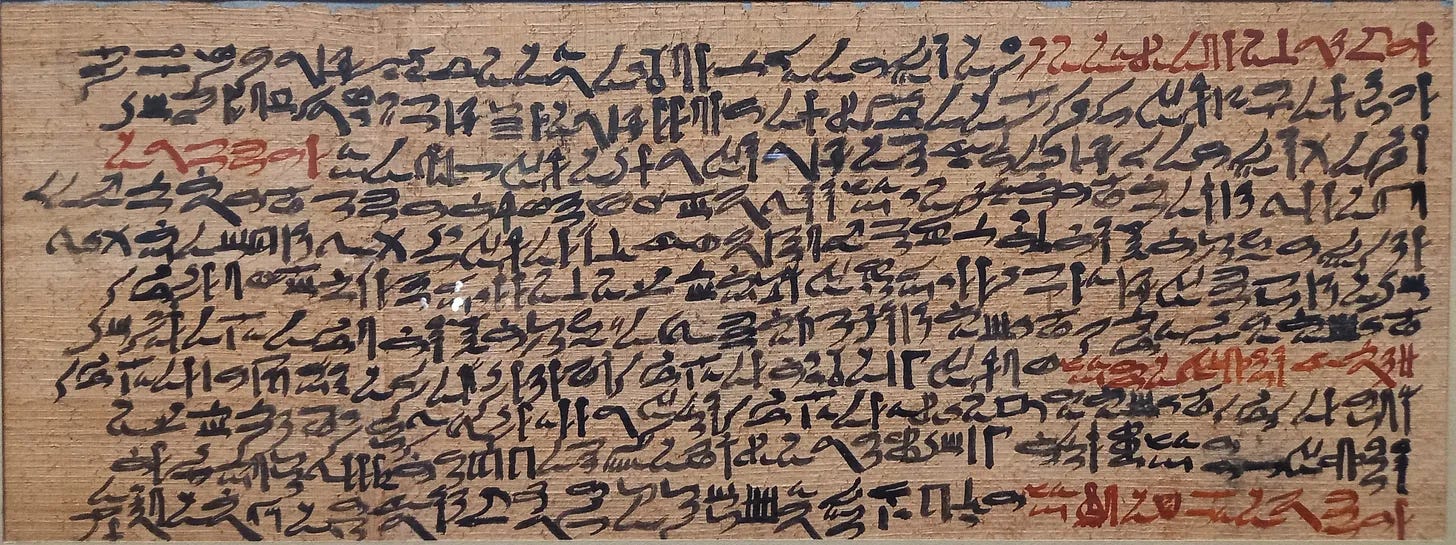

Ancient foundational texts—Torah, Qur’an, Gospels, Vedas—carry upon them hermeneutical strata accumulated over centuries. Each generation has commented, interpreted, used these texts for its own needs. These interpretations have sedimented like geological layers: rabbinical, patristic, juridical commentaries; theological dogmatizations (Trinity, redemption, nature of Christ); political instrumentalizations (justification of wars, colonizations, dominations); pedagogical simplifications (catechisms, vulgarizations); sclerosis in rituals emptied of meaning.

The text I hold in my hands is never naked. It bears the scars of everything that’s been done with it. My first task is not to “understand” it immediately, but to become conscious of these accumulations, like removing the layers of an old painting to find the original layer—not through sterile archaeology, but through reverence for the force of what resists wear.

Concrete examples:

The Torah read through the medieval prism of the Zohar is not the Torah read through a 21st-century historical-critical contextualization.

The Gospel of Matthew was “Christianized” (transformed into a doctrine of salvation) very differently from what the first Jewish communities of Jerusalem who composed it taught.

The Qur’an has known periods of interpretative closure (the “gates of ijtihad closed” in the 10th century) and periods of openness. Each political era has bent it to its needs.

Recognizing these layers is not skepticism; it’s hermeneutical honesty. It’s seeing how truth has been transmitted and how it may have been locked in dead dogmas.

The school of suspicion: Marx, Nietzsche, Freud

Paul Ricœur forges the concept of the “school of suspicion“ by bringing together three thinkers who all three practiced a hermeneutics of demystification. Marx suspects that consciousness is determined by economic infrastructures. Nietzsche suspects that truth, morality and religion hide the will to power and resentment. Freud suspects that the conscious ego is governed by repressed unconscious forces.

For Ricœur, this hermeneutics of suspicion is necessary but insufficient. It practices the deconstruction of illusions—but it cannot stop there without falling into nihilism. For if all meaning is only illusion to be demystified, then reading becomes impossible: there’s nothing left to encounter in the text.

The creative dialectic: suspicion and restoration

Ricœur therefore introduces a creative tension between two opposed but complementary hermeneutical orientations:

The hermeneutics of suspicion—the “will to suspect”: it demystifies the illusions of consciousness, practices an archaeology of meaning (return to hidden origins: unconscious, economy, will to power), aims to unveil what is masked, repressed, distorted.

The hermeneutics of restoration—the “will to listen”: it restores the full meaning of symbols, myths, foundational texts, practices a teleology of meaning (orientation toward a promise, a vocation, a call), aims to welcome what gives itself in the symbol, the text, the word.

This dialectic is formulated in the famous axiom: “The symbol gives rise to thought.” The symbol is neither an enigma to decrypt (hermeneutics of suspicion alone), nor a transparent evidence (first naïveté), but a donation of meaning that calls for a creative interpretation.

Toward the second naïveté

One of Ricœur’s most important concepts is that of “second naïveté” or “post-critical naïveté.” It’s not a naive return to first belief, as if critique had never taken place. It’s a dialectical movement in three stages:

First naïveté: immediate belief, spontaneous adherence to religious symbols, myths, sacred texts.

Critique: passage through suspicion (Marx, Nietzsche, Freud), deconstruction, structural explanation, demystification.

Second naïveté: a mediated belief, passed through the sieve of critique, but which rediscovers the capacity to listen and welcome meaning without being naive in the first degree.

As Ricœur says: “In and through critique, tend toward a second naïveté.” This formula summarizes the entire orientation of his hermeneutics: one must cross the desert of suspicion to rediscover, on the other side, a living and responsible relationship to symbols and foundational texts.

Honest hermeneutics is not the flight from presuppositions, but their courageous clarification. It’s about learning to dialogue with the text knowing that I don’t arrive virgin, but refusing to let my approach violate or impoverish it. It’s a discipline: the one that consists of maintaining a creative tension between trust (the text has something to say to me) and critique (the text must not be a mirror of my projections alone).

III. Jewish hermeneutics: a rampart against dogmatics

“Elu ve-elu divrei Elohim hayyim”: Both are words of the Living God

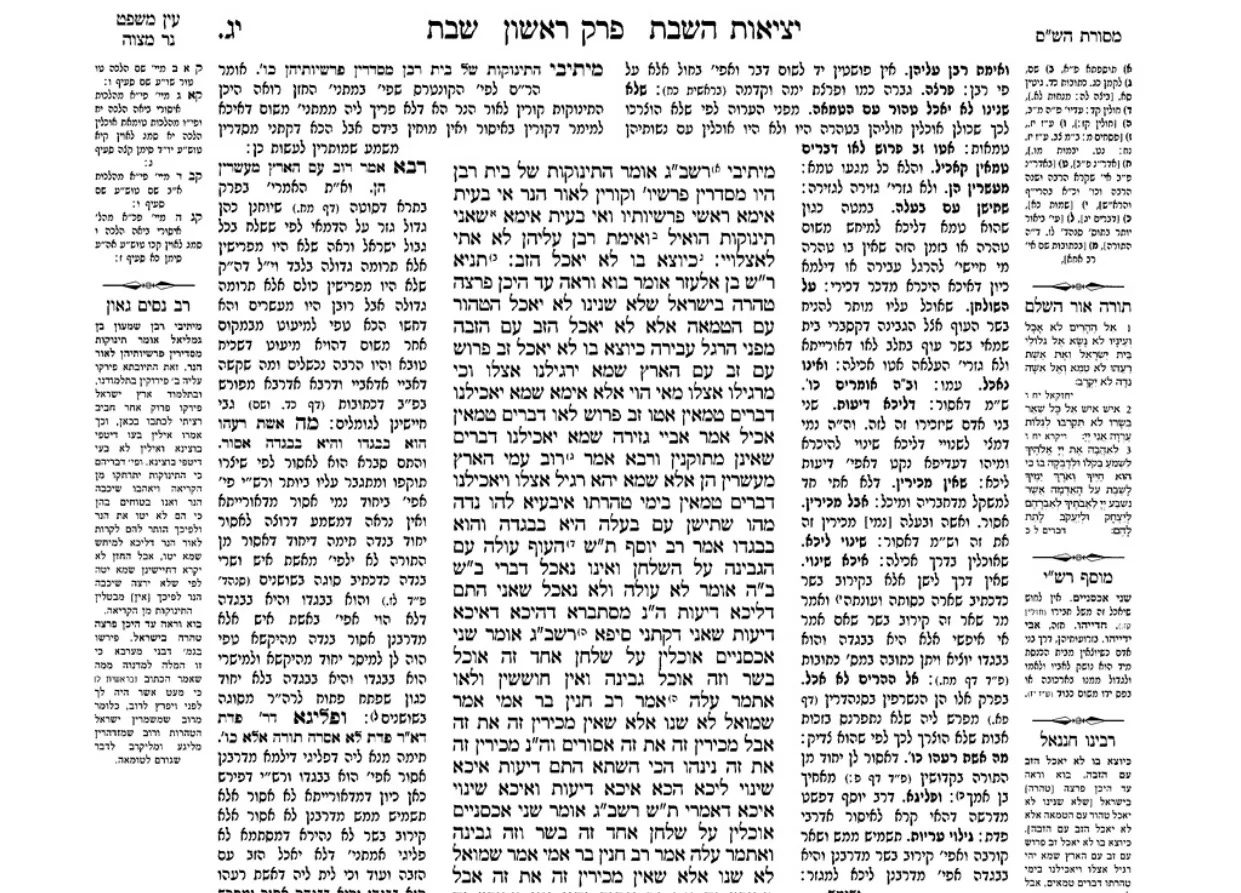

At the heart of Jewish hermeneutics lies a principle that perhaps constitutes one of the most revolutionary affirmations in the history of spiritual thought: “Elu ve-elu divrei Elohim hayyim”—”The words of some and the words of others are words of the Living God.”

This affirmation emerges in the Talmud (Eruvin 13b) after three years of disputes between the School of Hillel and the School of Shammai, two rabbinical academies that opposed each other on almost all halakhic (legal) questions. A heavenly voice (bat kol) intervenes to decide: both are right.

This formula must be understood in a conditional form: “If there are words of some AND words of others, then these are words of the Living God.” In other words: plurality itself is the condition of living truth. It’s not despite the contradiction that the two positions are true; it’s because of their dialectical coexistence that they manifest the divine word.

This implies a radically different conception of truth: it’s not monolithic (one single correct answer), but polyphonic (several legitimate answers in creative tension).

The mahloket: controversy as sacred principle

The mahloket (מחלוקת) is controversy, hermeneutical dispute between masters. But it’s not an accident, a dysfunction that should be resolved. It’s the very heart of the Talmud, its normal mode of functioning.

As a commentary specifies: “Controversy becomes an integral part of the production of law and constitutes the testimony of its vitality.” It’s no longer an exceptional case, but the normal mode of truth’s appearance.

Fundamental characteristic: no third term comes to suppress the contradiction. In Hegelian dialectic, thesis and antithesis are surpassed in a synthesis. In the Talmud, there is NEVER any synthesis. The two positions remain, alive, unresolved, in permanent tension.

As a commentator formulates it: “Between two masters who discuss, there is a void. The mahloqet proceeds from empty space, which is the original place of all questions.” This “void” is not a lack; it’s the space of hermeneutical freedom, the opening that prevents dogmatic closure.

A remarkable commentary breaks down the word mahloket into M-hlq-t: between the two letters of the word “death” (met = מת), duality (hlq) interposes itself and prevents death from constituting itself. Controversy prevents the death of thought. When a thought freezes into a single doctrine, it becomes “thought thought” (dead). The mahloket maintains “thinking thought” (alive).

Contrast with Christianity: councils and dogmas

Christianity, from its first centuries, took a diametrically opposed path. Faced with the plurality of interpretations on the nature of Christ, the Trinity, redemption, the Church convened ecumenical councils whose function was to definitively settle theological questions.

Each council produces a creed (symbol of faith) that all Christians must accept under pain of being declared heretics. This clear boundary between orthodoxy (right doctrine) and heresy (false doctrine) is accompanied by sanctions: excommunication, persecution, burnings, wars of religion.

In Talmudic Judaism, such a situation would have given rise to a mahloket: the two positions would have been recorded in the Talmud, debated, and neither would have been anathematized.

Marc-Alain Ouaknin: “Reading in bursts”

Marc-Alain Ouaknin, a french philosopher and rabbi, shows that Talmudic hermeneutics anticipates, enriches and surpasses modern philosophical hermeneutics. For Ouaknin, the Talmud is not merely a religious text; it’s a living hermeneutical practice, a model of reading that liberates meaning instead of freezing it.

The title of his major work, Lire aux éclats (1989), is programmatic. “Reading in bursts” (lire aux éclats) means several things at once: reading in a fragmented, burst manner (refusing linear and totalizing reading); reading until meaning bursts (pushing interpretation until significations multiply, disperse, open infinitely); reading in joy (bursts of laughter, amazement—Talmudic reading is erotic, playful, alive, not a pious chore).

Ouaknin shows that the Talmud structurally calls its readers to complete it. The Talmudic text is holed, enigmatic, contradictory by design. It resists immediate comprehension, not through obscurantism, but to arouse hermeneutical desire.

A Talmudic image that Ouaknin frequently uses: “How does the infinite that becomes text in the finitude of the text accept this finitude? A text—the Torah—is like God who is imprisoned in the finitude of a text.” And the answer is very important because it explains why there’s a sort of obsession with study: “The masters say that studying, giving infinite meaning, is liberating God from the finitude in which He accepted to enclose Himself to speak to men.”

This hermeneutics of reading is radical: to interpret is to liberate God. The human is responsible for God, responsible for His freedom. This joins Ricœur’s intuition according to which the text is not a dead object, but a living word that awaits being actualized in reading.

The refusal of all authority: Krishnamurti

Krishnamurti formulates in 1929 his most famous declaration: “Truth is a pathless land.” This affirmation has radical hermeneutical consequences. This means that no religious organization can lead to Truth, no creed or dogma can enclose Truth in a formula, no priest or guru (including Krishnamurti himself) can pose as an obligatory intermediary between man and Truth, no ritual or psychological technique can “produce” Truth.

And, by extension: no sacred text can be read as an “authority” to which one submits. This doesn’t mean sacred texts are “false” or “useless.” It means they can only be truly read if one refuses to give them an external authority that would short-circuit our direct observation of reality.

IV. Specificity of recent Texts: welcoming direct polysemy

A fundamental difference

Recent texts—like the Revelation of Arès or the Dialogues with the Angel—pose a hermeneutical question different from that of ancient texts. Ancient texts require that one deconstruct the accumulated historical layers to rediscover the original voice. Recent texts, for their part, have not yet known this sedimentation. But this doesn’t make them “easier” to read. On the contrary: they present an infinity of coexisting significations right now, without the reassuring filter of established commentaries.

Dialogues with the angel: deliberate enigma

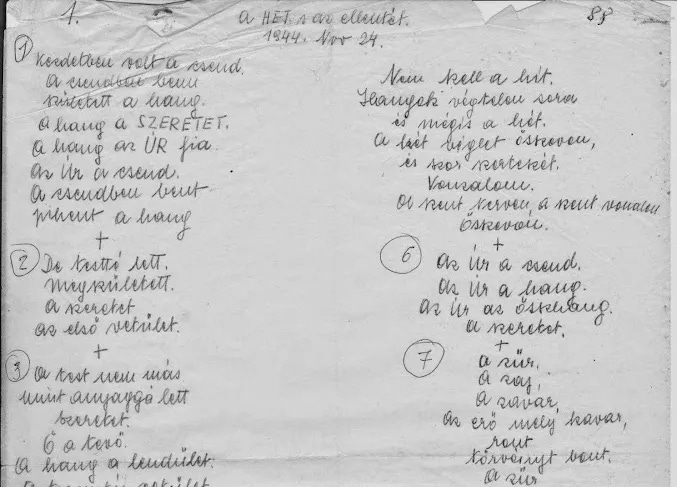

The Dialogues with the Angel, transmitted by Gitta Mallasz between 1943 and 1944 in occupied Hungary, are composed in a fragmentary, enigmatic, highly symbolic language. No doctrine to unfold, but resonances to let vibrate. Each sentence is itself a question addressed to the reader.

Take this example: “The Angel is my vivifying half and I am his vivified half.” This sentence refuses to be clarified. It plays on androgyny (fusion of sexes), duality (two beings who form only one), inverted hierarchy (who vivifies whom?), passivity-activity (vivifying/vivified), invisible-visible (the Angel = the invisible, me = the visible), consciousness-matter (one thinking, the other acting).

Gitta could have clarified, formulated a doctrine. She chose to leave the sentence in suspension, rich with its unresolved tensions. It’s a poetic and hermeneutical choice. This means that when one reads the Dialogues, one must not seek to resolve the ambiguities. One must settle into them, inhabit them as one inhabits a cathedral: complexity is the message, not an obstacle to overcome.

Revelation of Arès: architected ambiguities

The Revelation of Arès, transmitted by Michel Potay in 1974 and 1977, also presents deliberate ambiguities: who speaks? (Jesus? God? Mikal?) What meaning? (literal? symbolic? prophetic?) What call? (personal transformation? collective transformation? eschatology?)

These ambiguities are not “defects” to clarify, but riches to let resonate. The text possesses a poetic density independent of the explanations Potay may have given of it. And it’s precisely this openness that keeps it alive, not frozen in an orthodoxy.

“Reading in bursts”: each word as prism

Reading in bursts means recognizing that each word of a “sacred” text is a poetic crystal: it doesn’t possess one color, but a thousand. Depending on the angle by which I illuminate it—the angle of my present suffering, my intimate quest, my existential questions—the crystal will send back a different facet to me.

Take the word “Silence” in the opening of the Dialogues: “In the beginning was Silence.” What is this Silence? The absence of speech? The unexpressed fullness? The space of listening? Death? Gestation? Waiting? Eternity? None of these meanings is “wrong.” Each is legitimately inscribed in the word, waiting for the reader who will illuminate it through their own story, their own quest.

This is not a negative indeterminacy; it’s the very richness of poetic language. It’s also why the same text can speak to me differently each time I reread it—not because it changes, but because I change. And at each new angle of my existence, the crystal offers me a new resonance.

Three levels of resonance

Reading at three levels means that I never reduce the text to a single “correct interpretation.”

Level 1: Lexical-Poetic

The word in itself, its multiple vibrations, independently of my history. “Silence” vibrates with the concepts of totality, potentiality, eternity, death, gestation. These vibrations exist before I encounter them.

Level 2: Autobiographical-Intimate

What the word awakens in me on my personal path at this moment. If I’m going through an existential crisis, “Silence” may call to me as an appeal to recollection. If I’m fragmented by the noises of the world, “Silence” speaks to me of recentering. If I’m going through mourning, “Silence” may resonate as death or transformation. None of these readings is “wrong”—they’re all true for me, at this moment.

Level 3: Archetypal-Universal

What the text teaches about the human condition beyond ages. How Life emerges from primordial Silence = eternal question about origin. How the human can become “half of the Angel” = question about human participation in the divine.

These three readings don’t oppose each other; they mutually illuminate. That’s why, when I reread the text in six months, with a heart transformed by life, other resonances emerge: the text remains the same, but I have changed.

Hermeneutical synchronicity

One of the marvels of poetic reading of these contemporary texts is this faculty of “spontaneous consonance“ with ancient traditions. Without scholarly study, without “cultural references,” simply by reading with the heart, I discover myself in dialogue with Moses, Buddha, Rūmī, Francis of Assisi. It’s not because I’m “learned”: it’s because, beyond diverse forms, an Eternal Wisdom expresses itself.

A recent Word of Life, precisely because it remains open and non-dogmatic, lets this Wisdom circulate freely, crossing centuries and traditions like water finds its way in the ground. That’s why one can read the Dialogues with the Angel by “seeking echoes”—not as erudition, but as recognition: “Ah, this is what the ancients meant!”

V. Silence as pedagogy: learning to listen before speaking

Silence is not absence

We live in a world of incessant speech, reactivity, prefabricated responses. We have lost contemplative listening. Silence is not absence; it’s active fullness. It’s the space from which speech surges. It’s the implicit horizon without which each word falls dead.

Poetic reading of a foundational text requires the learning of silence—not as flight, but as the capacity to hold open a space in which the ancient or contemporary Word can resonate without being immediately domesticated. This silence is a discipline: it’s refusing mental reactivity, accepting the discomfort of waiting, letting oneself be questioned rather than seeking immediately to interpret. In this silence, the text begins to speak with its own voice, freed from my projections.

Method inspired by Lectio Divina

The practice of Lectio Divina (reading a short passage several times in silence) is not exotic or exclusively Christian. It’s a model of what it means to encounter a text.

First reading: welcome without analysis. Let the text resonate. “What does the text say?” not “What should I think of it?”

Silence of 5-7 minutes: it’s long, it’s like an eternity for the modern mind. Here, conditioning emerges: impatience, need for answer, automatic interpretation, flight toward reassuring meaning.

Second reading: meditation. “What does the text say to me today, for my life, for my questions?” Here, personal resonance begins, without replacing the text with a projection.

Silence again: let the gap deepen between what I heard and what I understood.

Third reading: prayer or response. It’s I who speak now, in dialogue with the text, not as submission, but as reciprocity of engagement.

Final contemplation: remain in silence, beyond words.

VI. The non-dogmatic ethical demand

The text interrogates me

The Words of Life are not doctrines to believe. They pose an existential question: how will I live? What justice will I serve? What is my share of responsibility in this world?

Deuteronomy says it with radical sobriety: “See, I have set before you today life and good, death and evil... I have set before you life and death, blessing and curse. Choose life, that you and your descendants may live.”

The Qur’an: “To each of you We have prescribed a law and a path. And if God had willed, He would have made you one community, but He wished to test you by what He has given you.”

The Gospel: “Love one another” is neither a codified morality nor sentimentality. It’s a demand that places me before my own resistance, my own conditioning of fear.

Reading the Words of Life is not an intellectual matter. It’s entering into a Covenant: accepting to be questioned by a demand that exceeds my capacities, that tears me from my habitual complacency, that makes me responsible before the other and before my own hidden essence. This demand doesn’t need to be wrapped in a dogma to be true. It suffices for me: it puts me to work, day after day, in a way that transforms my way of seeing and acting.

Responsibility without guilt

Authentic reading doesn’t end when I close the book. It continues in the way I live, in the choices I make, in the way I inhabit this demand without ever being able to completely satisfy it.

This liberates from dogmatism: I don’t have to believe an exact creed, but I must embody a concrete responsibility. And this embodiment will always be imperfect, always in question. It’s precisely this assumed imperfection that keeps me humble, that prevents me from claiming to possess truth, that maintains me in the search and leaves me open to dialogue.

Conclusion: toward a sovereign and responsible reading

Truly reading a sacred text therefore perhaps requires a fourfold discipline.

With Ricœur, I learn to cross the desert of suspicion without losing the capacity for listening. I recognize that my presuppositions exist, I clarify them, I submit them to critique—but I refuse to stop at the cynicism that dissolves all meaning.

With Talmudic hermeneutics as Ouaknin deploys it, I accept that the text remains infinitely open, irreducible to a closed doctrine. I honor the mahloket, controversy as sacred principle. I recognize that “the words of some and the words of others are words of the Living God”—that plurality itself is the condition of living truth.

With Krishnamurti, I observe how my conditionings project onto the text their own fears and desires. I refuse to give the text an authority that would short-circuit my direct observation. I practice observation without the observer, this clarity of vision where conditioning dissolves by itself.

With Gurdjieff, I recognize that depending on which “I” reads at this instant, the text will say something different. I practice self-remembering, this presence to myself that unifies my reading and makes it coherent. I understand that truly reading requires preliminary work on being, not just an accumulation of knowledge.

These four approaches don’t oppose each other: they complement each other to form a hermeneutics of freedom, where reading is no longer just interpreting, but becoming capable of encountering.

This freedom is not that of arbitrariness (”everyone reads what they want”). It’s a responsible freedom: I’m free in my interpretations, but I must answer for their consequences. I’m free to question the text, but I must accept that it questions me in return. I’m free to refuse all external authority, but I must assume the ethical demand that emerges from dialogue with the text.

Neither dogmatism, nor relativism. Neither blind submission, nor cynical rejection. A sovereign and responsible reading that honors the dignity of the text as much as the dignity of the reader. A reading that recognizes that truth is not monolithic, but polyphonic. That it’s not possessed, but sought in dialogue. That it never freezes into dead doctrine, but always remains alive, open, in movement.

This is the reading I seek to practice. This is the reading I invite everyone to practice. Not as a technique to master, but as a way of inhabiting the world—with reverence, with demand, with humility, with joy.

For to truly read the Words of Life is to accept being transformed by them. It’s to consent that our life itself becomes a reading—an incarnated interpretation, imperfect, always in question, but faithful to the call that has been addressed to us.

Jérôme Nathanaël

© 2026 - Dialogues of the New World by Jérôme Nathanaël

To go further:

Paul Ricœur (1913-2005)

French philosopher of hermeneutics and personalism, who developed a thought articulating the hermeneutics of suspicion (Marx, Nietzsche, Freud) and the hermeneutics of restoration, aiming for a post-critical “second naïveté” capable of welcoming the full meaning of symbols.

Major works:

De l’interprétation. Essai sur Freud (1965)

Le Conflit des interprétations (1969)

La Métaphore vive (1975)

Temps et récit (3 volumes, 1983-1985)

Soi-même comme un autre (1990)

Marc-Alain Ouaknin (1957-)

French philosopher and rabbi, specialist in the Talmud and Jewish thought, who renewed contemporary hermeneutics by showing that Talmudic reading anticipates and surpasses modern hermeneutics through its structural refusal of any dogmatic closure of meaning.

Major works:

Lire aux éclats. Éloge de la caresse (1989)

Le Livre brûlé. Philosophie du Talmud (1986)

Concerto pour quatre consonnes sans voyelles. Au-delà du principe d’identité (1991)

Méditations érotiques. Essai sur Emmanuel Levinas (1992)

Bibliothérapie. Lire, c’est guérir (1994)

Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986)

Indian philosopher and spiritual teacher who dissolved the Order of the Star in the East in 1929 to affirm that “Truth is a pathless land,” developing a radical thought on the total conditioning of the mind and observation without the observer as a path to liberation.

Major works:

Freedom from the Known (1969)

The Flight of the Eagle (1971)

Commentaries on Living (1956-1960)

The First and Last Freedom (1954)

This Light in Oneself (posthumous, 1999)

Georges Gurdjieff (1866-1949)

Spiritual teacher of Armenian origin, founder of the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man, who taught that the ordinary human being is a multiplicity of contradictory and mechanical “I’s,” and that only self-remembering can lead to a unified consciousness.

Major works:

Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (posthumous, 1950)

Meetings with Remarkable Men (posthumous, 1963)

Life Is Real Only Then, When “I Am” (posthumous, 1975)

Views from the Real World (posthumous, 1973)

In Search of the Miraculous (by P.D. Ouspensky, 1949)

Gitta Mallasz (1907-1992)

Hungarian graphic artist of Jewish origin, who transcribed between 1943 and 1944 (during the Nazi occupation of Hungary) a series of spiritual interviews with a voice she calls “the Angel,” constituting one of the most powerful mystical testimonies of the 20th century.

Major work:

Talking with Angels (complete annotated edition, 1988 English / 1990 French integral edition)

With Françoise Maupin, Les Dialogues tels que je les ai vécus (1984)

With Roger Bret, Les Dialogues, ou l’enfant né sans parents (1986)

With Dominique Raoul-Duval, Les Dialogues, ou le saut dans l’inconnu (1989)

With Dominique Raoul-Duval, Petits Dialogues d’hier et d’aujourd’hui (1991)

Michel Potay (1929-2025)

French prophet, former Orthodox priest, who claims to have received in 1974 and 1977 (in Arès, France) a revelation he calls La Révélation d’Arès, calling for a radical ethical transformation of humanity through the return to penitence, love, and spiritual freedom.

Major works:

The Revelation of Arès (1995)

And what you shall have written 4 (1997)

And what you shall have written 3 (1993)

And what you shall have written 2 (1991)

And what you shall have written 1 (1990)

Interested in this publication? Help spread the word!

If you appreciate the approach of these Dialogues, help introduce them to others who might enjoy discovering them!