Quentin, beaten to death for an idea — barbarism has kept its appointment

Anatomy of a symptom — An urgent plea for a civilisational renewal grounded in our common humanity

This post is the author’s own translation of the original French version.

Current Affairs

On February 14, 2026, while many were exchanging Valentine’s Day declarations of love, a 23-year-old man was lynched and died in Lyon. His name was Quentin Deranque. He was a mathematics student and a philosophy enthusiast who sang in his parish choir.

Two days earlier, on February 12, he was near Sciences Po Lyon, the city’s prestigious political science institute, where the Némésis collective held a counter-demonstration against a conference by Rima Hassan, a member of the European Parliament for the far-left La France Insoumise party. Quentin held nationalist convictions and moved in Lyon’s Catholic traditionalist circles. Némésis presented him as a member of its security detail. However, his family and their lawyer formally contested this characterization. They stated that Quentin was “neither a security agent nor a member of any protection service,” had no criminal record, and defended his convictions in a nonviolent manner.

What is certain is what followed: the confrontation between the two groups of militants turned into a bloody battle. Pursued by a group of several dozen far-left activists for more than two kilometers, he was knocked to the ground and struck repeatedly on the head. He was found unconscious by the banks of the Rhône. He never recovered. The autopsy revealed a fatal brain injury. He was beaten to death for what he represented.

This is not an ordinary criminal case. It is a symptom, and it calls not for a partisan reaction but for courageous clarity.

Two commitments, two logics, two levels of responsibility

Much of the international press has simply described Quentin as a “far-right activist.” While not inaccurate, this description is incomplete. Honest analysis requires us to draw finer distinctions than those that fit a headline.

Founded in 2019, the Némésis collective presents itself as an identitarian feminist movement. It denounces sexual violence against women in public spaces and insists on its connection to migration. The collective positions itself as a defender of what it calls “European civilization.” The collective’s origin touches on a genuine concern. After the mass sexual assaults on New Year’s Eve in 2016 in Cologne, a significant segment of the feminist left remained silent about the perpetrators’ origins for fear of fueling racism. This left a rhetorical and political vacuum that identitarian movements were quick to fill.

The vacuum was real, but the way Némésis chose to fill it is far more questionable. The collective’s discourse racializes sexual violence, designates Muslim immigrant men as a structural threat to women, reduces wearing the veil to “political Islam activism,” and promotes a conservative, exclusionary vision of femininity. Némésis is neither a neo-Nazi organization nor a simple women’s rights movement. It is a radical right-wing identitarian collective whose rhetoric stigmatizes an entire ethno-religious category of the population. This is both ideologically problematic and socially dangerous, even when no physical violence is incited.

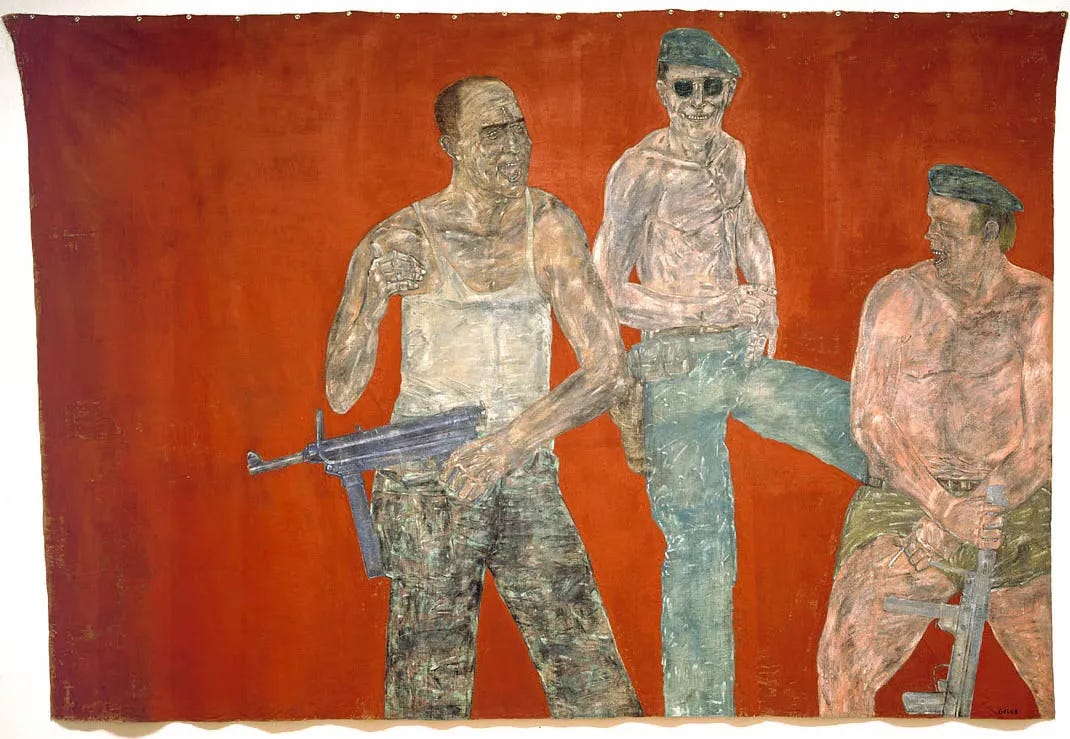

This is precisely the fundamental difference with La Jeune Garde Antifasciste, the group from which Quentin’s assailants appear to have come, according to judicial sources. Founded in 2018 by Raphaël Arnault, who was subsequently elected to the French parliament under the La France Insoumise banner, this far-left collective was structured around combat training and planned physical confrontations with far-right groups, according to French authorities. This is precisely why the government dissolved it in June 2025. The difference is not one of degree, but of nature. Professing radical ideas is one thing, however objectionable. Organizing groups of masked men to chase and beat political adversaries in the street is another matter entirely, and it is this second logic that killed Quentin Deranque.

I want to be clear: I do not share Némésis’s positions or their vision of a “European civilization” reduced to an identitarian fortress closed in on itself. I believe in a new civilization that is open and founded on dialogue between human beings. It is a civilization that acknowledges the complexity of the world and seeks common solutions in a spirit of mutual goodwill. However, rejecting their ideas does not authorize me to equate them with killers or to claim that legal identitarian discourse is equivalent to deadly lynchings. Ethical clarity requires these distinctions.

The political atmosphere that makes this possible

However, it would be insufficient to look only at these two fringe groups, ignoring the rest of the political landscape. Quentin’s death occurs against a broader backdrop in which elected political representatives have progressively abandoned debate in favor of designating opponents as enemies.

La France Insoumise, comparable in spirit and method to the most radical wing of left populism found in several Western democracies, has popularized a conflictual grammar in which opponents are entities to be delegitimized rather than interlocutors. The persistent accusations of antisemitism against several of its elected officials — accusations that they contest but that their handling of the October 7, 2023, massacres has substantially fueled — betray a structural difficulty in clearly naming hatred when it presents itself in a politically convenient guise. Refusing to label the massacre of 1,200 people based on their Jewish identity as an antisemitic crime in favor of a geopolitical framework of “resistance” is not a trivial semantic debate. It authorizes a narrative in which the dehumanization of certain people becomes understandable, if not justified.

Rima Hassan, the central figure in this polarizing debate, embodies these contradictions. She is genuinely committed to the Palestinian cause but multiplies militant appearances and statements that, according to her critics, blur the line between humanitarian advocacy and legitimizing hate speech. Multiple proceedings for “apology of terrorism” have been opened against her in France, none of which have resulted in convictions thus far; all are still under judicial review. However, these cases outline a political space where ambiguity is systematically cultivated, with consequences for the social climate that cannot be ignored.

From words to blood: the mechanics of dehumanisation

There is a slippery slope between words and actions. This slope is not inevitable; millions of people hold radical opinions without ever raising a hand against anyone. However, it becomes dangerous when language ceases to acknowledge the full humanity of others.

It becomes dangerous when a radical-right activist is seen as a “fascist” to be neutralized, when a pro-Palestinian citizen is seen as a “potential terrorist” to be crushed, and when a university conference is seen as “an act of war” and a counter-demonstration as “a nest of Nazis.” In this context, physical violence is merely the natural extension of the discourse. All that’s needed is an opportunity and the impunity of numbers. The slogans have done their work; they have stripped the opponent of his humanity.

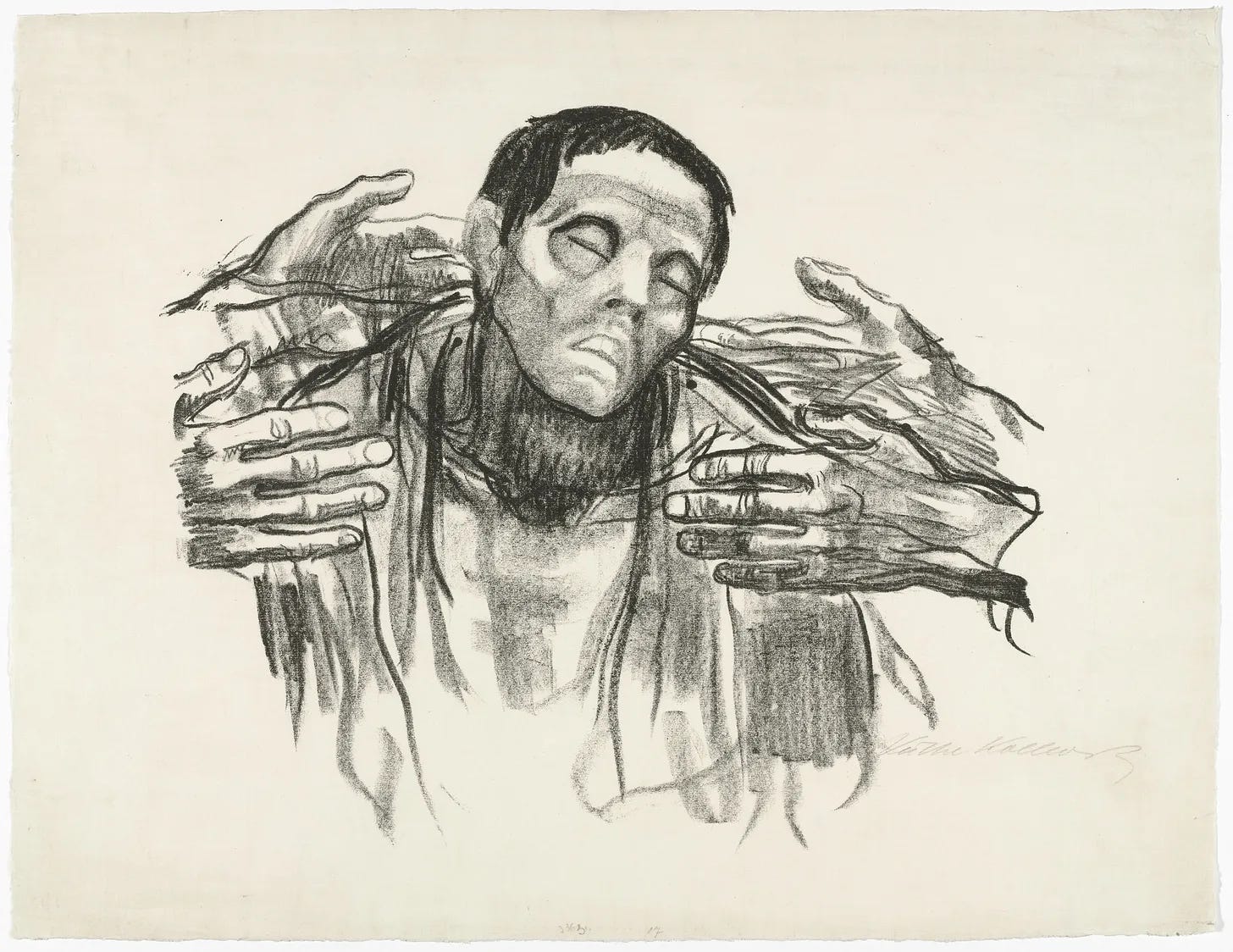

The lynching of Quentin teaches us precisely this: a group of individuals pursued, surrounded, and beat a man already on the ground—some of them masked, that is, knowingly—because they had absorbed into their militant imagination that this man deserved to live less than others. This is not uncontrollable madness; it is ideological coherence carried to its most bestial conclusion.

It is the return of militia logic: organized groups hunting and beating their political opponents in the streets. History has seen its darkest forms, and we believed we had learned from them. Every form of thought that claims allegiance to humanity must unambiguously condemn this, regardless of political affiliation.

The shattered mirror of a society that has lost its common reference points

This tragedy forces us to face something we generally prefer to avoid: modern societies have entered a phase of profound dislocation of their shared ethical reference points. This is not because people are fundamentally worse than before, but because the symbolic structures that once contained conflict—respect for the law, a culture of debate, recognition of shared dignity, and the spiritual foundation of “thou shalt not kill”—have eroded faster than our collective capacity to register it.

Social media has created echo chambers where each group reinforces its worst fears and darkest judgments about others. Political spectacle has replaced deliberation with conflict. In this ethical and spiritual void, violence fills the void left by words. Rather than arguing and seeking compromises from which each interlocutor might benefit, violence imposes itself, provokes fear, and forces the other to yield.

Quentin’s death is a tragedy, but we must not allow it to blind us to an even more troubling tragedy: young people on both sides are so deprived of inner resources, a shared language, and spaces for genuine encounters that they can no longer see their political adversaries as anything other than threats to eliminate. This is the true poverty of our age—not only material poverty, but also the poverty of the soul that makes it impossible to look the other person in the eye and recognize that, despite all that divides us, he is made of the same clay and has the same essential humanity.

The urgency of recovering our common humanity

I want to speak in my own name and clearly dissociate myself from all forms of radicalism — whether political, discursive, or physical — that reduce the world’s complexity to slogans and reduce people to symbols to be destroyed.

The crises we are experiencing—the migration crisis, the identity crisis, the geopolitical crisis, the ecological crisis, and the crisis of meaning—are real and profound. They deserve better than tribal responses. These crises call for slow, humble thinking capable of holding together seemingly contradictory realities: migrants can be both victims of unjust systems and perpetrators of violence; defending Israel and standing in solidarity with Palestinians are not mutually exclusive; and love for European civilization and openness to other cultures can coexist. Holding these paradoxes alive without hastily resolving them is the most courageous act of thought available to us today.

This requires a type of work that political discourse will never perform for us: work on ourselves, our own hatred, our own absolutist certainties, and our tendency to reduce others to caricatures in order to maintain our identities. This work is spiritual in the deepest sense—not religious in the narrow sense, but interior, patient, and demanding. It involves forgiveness—not naive forgetting, but the sovereign decision not to allow hatred of the other to define who we are. It passes through dialogue—not strategic negotiation, but the authentic willingness to be changed by what the other has to say. It passes through humility—the recognition that my interpretation of the world, however legitimate, is incomplete in the face of the infinite complexity of reality.

The absurd brutality of Quentin Deranque’s death can be an invitation. Not to vengeance or political escalation—his parents themselves called for calm with remarkable dignity. Rather, it should prompt us to ask ourselves what kind of world we want to live in. Do we want to live in a world where people die for what they believe in, or do we want to live in a world where we learn, even painfully, to talk to one another?

Quentin was twenty-three years old. He loved mathematics and sacred music. He died because someone decided that belonging to an idea stripped him of his right to life. May his death teach us what we had not learned any other way: that the humanity of others cannot depend on their opinions. It is precisely this fragile and demanding principle that defines a civilization worthy of that name.

Jérôme Nathanaël — New World Dialogues

Current Affairs, February 2026

Found this worth reading? Pass it on!

If the approach of these Dialogues speaks to you, help others find their way to them — they might be glad you did.