The desire to be: meditation on an initiatory poem by René Daumal

Journey of radical transformation: from the illusion of possession to the necessity of becoming

René Daumal, seeker of truth and disciple of enlightenment

René Daumal was born on March 16, 1908, and died on May 21, 1944. He was a French writer and poet whose fame is more established in the English-speaking world than in his native France. This differential recognition perhaps reflects French culture’s difficulty in embracing its children who venture into the perilous territory of radical metaphysical quests. French culture often prefers to celebrate virtuosos of the word over explorers of being. Daumal belongs resolutely to the latter category: seekers who prioritize inner transformation over literary performance. Nevertheless, his work displays remarkable mastery of poetic and novelistic expression.

He is the author of La Grande Beuverie, a novel presenting a caustically humorous critique of society’s workings and human behavior’s pretenses, and the allegorical novel Le Mont Analogue, subtitled “A novel of symbolically authentic, non-euclidean mountain-climbing adventures.” These two works are not mere literary exercises but stem directly from Daumal’s friendship with Alexandre de Salzmann, a student of G. I. Gurdjieff, and the radical self-work he undertook as a result. Encountering Gurdjieff’s teachings marked a decisive turning point for Daumal, transforming his youthful intuitions into a rigorous discipline and his romantic aspirations into daily asceticism.

He also wrote numerous articles on Hindu spirituality, which he studied in texts after learning Sanskrit at a young age. This demonstrates the thirst for direct knowledge of sources that characterizes true spiritual seekers. He also left behind enlightening poems, such as La Guerre Sainte (The Holy War), which is a parable of the inner war he waged to attain true being. This struggle is recognized as the true jihad by all authentic traditions: the fight against our automatic mechanisms, comfortable illusions, and existential slumber.

He died of tuberculosis at the age of 36. He had probably contracted it at a younger age by poisoning himself with tetrachloromethane (CCl₄). He used this chemical to kill the beetles he collected and to deliberately immerse himself in comatose-like states of intoxication. These extreme experiences resemble what some would later call near-death experiences. This approach testifies to the sometimes dangerous intensity of his quest.

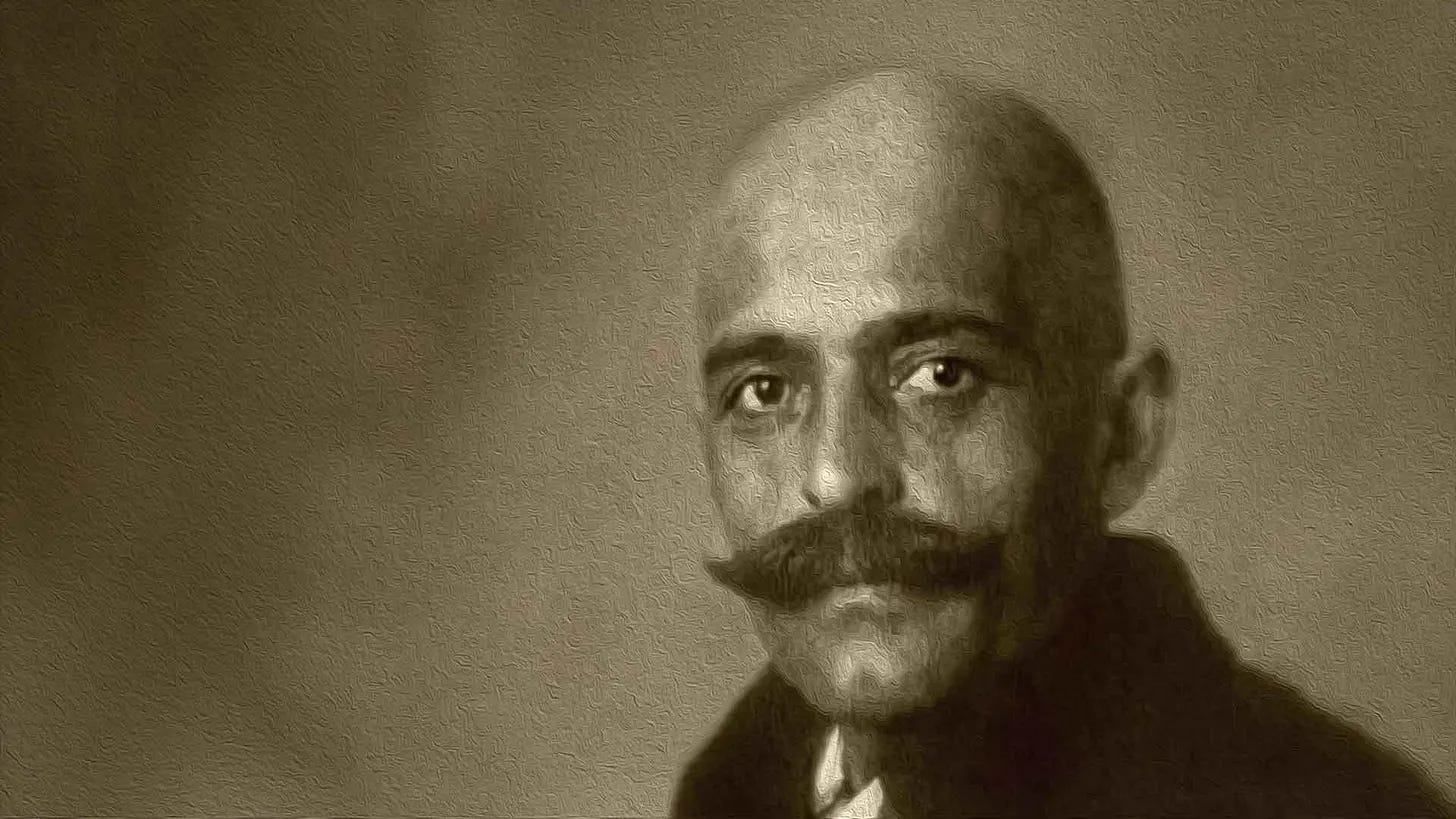

In 1928, René Daumal founded the magazine Le Grand Jeu in Paris with Roger-Gilbert Lecomte, Roger Vailland, and painter Josef Síma. It was a cry of revolt against a rationalist West that had forgotten the core of absolute truth, as stated by “the Vedic Rishis, the Kabbalist Rabbis, the prophets, the mystics, the great heretics of all time, and the true poets,” notably Rimbaud. In 1930, Josef Síma painted a portrait of René Daumal that captures the burning intensity of this young man in search of the absolute. The magazine published three issues between 1928 and 1930, but the fourth issue was never published.

After the magazine ceased publication, when the dazzling intuitions of youth called for method and discipline, Daumal encountered the teachings of Gurdjieff. He followed and put these teachings into practice until his death, finding in them the structure necessary for fulfilling his deepest aspirations.

Gurdjieff’s teachings: a framework for understanding the poem

To fully grasp the significance of Daumal’s poem about the desire to exist, it is helpful to review some key concepts from the teachings of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff. At the beginning of the 20th century, this Caucasian master developed a system integrating Eastern and Western wisdom into a practical synthesis for contemporary humans.

Gurdjieff taught that ordinary people live in a state of sleep: an existential somnambulism where the individual believes he is awake, conscious, and in control, when he is actually functioning mechanically. He reacts automatically to external and internal stimuli and remains a prisoner of habits, conditioning, and identifications that constitute his ego, or what Gurdjieff called the “false personality.”

From this perspective, ordinary human beings do not possess any real inner unity. They are a multiplicity of fragmented and contradictory “selves” that follow one another according to circumstances. Each “self” momentarily takes itself to be the center of the person and speaks on its behalf without any real continuity or coherence. This fragmentation explains why we make decisions we don’t keep, experience overwhelming emotions, and have thoughts that arise without conscious direction. Gurdjieff made a radical distinction between “personality,” the social and psychological construct consisting of imitations, roles, borrowed opinions, and defense mechanisms, and “essence,” the authentic but generally underdeveloped core of the human being—that which is truly original and unique within us.

From Gurdjieff’s perspective, working on oneself consists of developing this essence and creating a true inner unity, which he called the “Real Self” or the “Inner Master.” It also involves gradually awakening from the sleep-like state in which we spend our existence. This work requires conscious effort and voluntary suffering—that is, accepting the dissipation of our illusions, recognizing our true state, and persevering in exercises and self-observations that enable this transformation. Gurdjieff also emphasized the notion of “self-remembering,” which consists of dividing one’s attention between the object of one’s activity and one’s presence while performing that activity. This creates a state of consciousness superior to ordinary consciousness.

In light of these teachings, Daumal’s poem reveals its full depth and technical precision. It is not an abstract poetic meditation, but rather a cartography of states of consciousness and stages of spiritual awakening traced by someone who was walking this arduous path.

The poem: a map of awakening in eight stages

René Daumal was a great seeker of truth and a mountain enthusiast who understood that climbing peaks was a living metaphor for, and a concrete practice of, spiritual elevation. His poem on the desire to be summarizes the journey that leads human beings from their ordinary state to the realization of the need for spiritual development and, therefore, for self-improvement in order to attain a fulfilling life.

Each line of the poem marks a stage in the process of disidentification and awakening. Here is what it tells us:

“I am dead because I lack desire,

I lack desire because I think I possess,

I think I possess because I do not try to give;

In trying to give, you see that you have nothing,

Seeing that you have nothing, you try to give of yourself,

Trying to give of yourself, you see that you are nothing,

Seeing that you are nothing, you desire to become,

In desiring to become, you begin to live.”

The illusion of possession and spiritual death

“In desiring to become, you begin to live,” René Daumal tells us in a conclusion that retrospectively illuminates the entire journey. We then better understand the meaning of the first sentence: “I am dead,” which implies spiritual life because I have no desire for it. I have no desire for it because I believe that life boils down to having and accumulating possessions rather than developing my being and accessing a broader dimension. This statement is a brutal diagnosis of the ordinary state of humanity. It is similar to what Jesus said when he told us to “let the dead bury their dead” and what Sufi mystics said about the carefree, distracted man who is absent from himself.

This spiritual death is not like physical death. It is an absence of true life within biological activity itself—an existence reduced to mechanical, vegetative, and reactive functions. It is deprived of the specifically human dimension: awakened consciousness, presence to oneself, and the capacity for true, unconditioned choice. In Gurdjieffian terms, this death refers to the state of the machine man: a biological automaton that functions according to established programs without ever accessing the inner freedom that defines an accomplished human being. Why does this state of death persist? Because there is no desire to escape this condition; there is no aspiration for something greater, more real, or more alive.

This first sentence tells us a lot in a few words: “I am dead because I lack desire; I lack desire because I think I possess.” I am dead to spiritual life because I do not seek it. I do not seek it because I am content to possess goods and objects. This gives me an illusion of security and identity, which is enough for me. Contemporary society, with its cult of consumption and obsession with material accumulation, meticulously maintains this illusion. It makes incessant promises of happiness through acquiring new objects, experiences, and statuses. This extinguishes spiritual desire under successive layers of artificially created, outward-looking desires.

However, as Daumal implicitly suggests, we can broaden the meaning of “possess” beyond material possession. We can talk about possessing knowledge, diplomas, social recognition, power over others, psychic powers, healing abilities, and paranormal faculties. Daumal warns us with lucidity that possessing such powers does not necessarily mean entering spiritual life, which involves working on one’s being rather than one’s having, however subtle it may be. How many contemporary spiritual seekers stray into the quest for powers—or siddhis, as they are called in the Hindu tradition—and imagine themselves progressing spiritually when, in reality, they are merely enriching their arsenal of possessions? They are merely shifting the mechanisms of greed and identification that chained them to the material plane to the subtle plane!

The test of giving and the discovery of inner emptiness

The text continues with relentless logic: “I think I possess because I do not try to give. In trying to give, you see that you have nothing.” This proposition deserves careful consideration because it reveals the mechanism by which the illusion is maintained. As long as we don’t truly try to give, we can believe that we have something valuable, that our lives are full, and that we have something to share. It is the very act of wanting to give that reveals the emptiness of our supposed possessions and exposes the futility of our accumulations. It reveals that we hold nothing essential.

Remember that René Daumal wrote this dry text to provoke reflection rather than to offer illusory consolations. He resolutely places himself on the level of spiritual life rather than on the level of ordinary social exchanges. He tells us that when we try to give something essential—to pass on something that could truly help another person develop—we discover that unless we have undertaken authentic personal development and worked on ourselves in the Gurdjieffian sense, we have nothing fundamental to pass on. We have nothing that can truly awaken, elevate, or transform another person.

This discovery can be devastating to the ego, which is identified with knowledge, opinions, culture, and status as an educated or spiritually advanced person. People can come to understand that what they have is worthless and that they have nothing that stands up to authentic spiritual demands when they desire to give something essential or aspire to offer something truly valuable to others. One can own an entire library of sacred books and still not have integrated a single truth into one’s being. One can know all the sutras and mantras by heart and still not have transformed a single fault. One can speak eloquently of compassion, presence, and awakening and still not have developed the slightest real capacity in these areas.

Then, realizing that he has nothing essential to give, a person arrives at the following realization: he decides to give himself. “Seeing that you have nothing, you try to give of yourself; trying to give of yourself, you see that you are nothing.” This passage marks an intensification of the existential and spiritual crisis. After discovering that our possessions are vain, we discover that our very being is insubstantial. In trying to give themselves, human beings confront their internal contradictions, inner instability, lack of unity and continuity that characterizes their ordinary state, and lack of fulfillment.

This experience corresponds exactly to what Gurdjieff called the “shock of awareness” of our true state. We discover that we are not a unified “I,” but rather a multitude of contradictory “I’s.” We realize that we lack a genuine will, possessing only fleeting desires. We acknowledge that we are not fully conscious, but rather, we are immersed in a state of sleep. We recognize that we do not truly exist in the strongest sense. How can we give ourselves if we do not exist in a unified and conscious way? How can we offer our presence if we are absent from ourselves? This discovery can lead to despair or, as the rest of the poem shows, to a genuine desire for transformation.

The desire to become and entering into true life

“Seeing that you are nothing, you desire to become. In desiring to become, you begin to live.” These last two propositions mark a decisive turning point: the moment when the destruction of illusions becomes creative rather than merely destructive, and when the relentless diagnosis of our condition opens up the possibility of transformation. Recognizing our own nothingness is not a nihilistic observation that leads to resignation or depression. Rather, it is a liberating vision that dissolves false identifications and enables the emergence of an authentic desire to become. This desire is to develop a true being and build an inner unity — the “real I” of which Gurdjieff speaks.

This desire to become is the driving force behind spiritual work—the energy that enables us to persevere in conscious efforts and accept the voluntary suffering inherent in any real transformation. It is no longer the desire to possess, which characterized the state of spiritual death; rather, it is the desire to be, to fulfill oneself, and to realize the dormant potentialities of our essence. This desire defines true life: “in desiring to become, you begin to live.” In its fullest sense, life begins with the aspiration to transform oneself, with commitment to the path of spiritual development, and with the start of work on oneself.

This final formulation reveals a paradoxical truth: we only truly begin to live when we recognize that we were dead, attain being when we accept that we were nothing, and desire authentically when we cease to believe that we possess anything. Spiritual life begins with dying to illusions, being born into awareness of our true condition, and awakening the desire for transformation, which marks our entry into the process of becoming truly human.

Encountering others as a revelation: the relational dimension of awakening

This text is so radical and dense that each of its parts would require a lengthy discussion, given the depth and multiplicity of its implications. It reveals what may be the most essential yet neglected teaching in contemporary spiritual approaches. Daumal describes the discovery that occurs when we encounter another person in the context of a relationship within the intersubjective space where our desire to give something essential manifests itself.

When René Daumal realizes that he has nothing of value to offer the other person and that he is not sufficiently developed or accomplished to be worthy of this essential gift, he understands the significance of this encounter. This relational dimension of spiritual awakening deserves our attention as it contrasts sharply with popular spiritual quest imagery of withdrawal from the world, meditative isolation, and escape from complex or distracting human relationships.

Daumal tells us that it is precisely in the encounter with the other, in the desire to transmit, and in the aspiration to help someone else on their path that our true state is revealed. The other person becomes a merciless yet liberating mirror and a catalyst that precipitates a beneficial crisis of awareness. As long as we remain alone with our practices, meditations, and spiritual readings, we can maintain the illusion of progress, construct a flattering image of our development, and identify with our experiences and intellectual understandings.

As soon as we decide to help others by accompanying them in their transformation and offering them something that can truly awaken them, rather than giving them superficial advice or passing on bookish knowledge, we are confronted with the crucial question: What do I have to give? Who am I to claim that I can guide someone else? What transformation have I actually accomplished within myself? Confronting others with the desire to give is therefore a decisive test that reveals our true level of being, not our apparent level of knowledge or practice.

Gurdjieff emphasized the importance of group work, considering that the friction, relational difficulties, projections, and resistances that emerge in a collective context are irreplaceable material for personal growth. We cannot truly know ourselves in isolation because our defense mechanisms, identifications, and illusions only manifest fully in relationships. Others force us to step outside our comfortable mental constructs and confront our reality through their mere presence, reactions, and needs.

Resonances with universal spiritual traditions

The mapping of awakening proposed by Daumal in his poem is reflected in many spiritual traditions, attesting to its universal truth rather than its literary originality. In Buddhism, the path begins with the noble truth of suffering (dukkha), corresponding to Daumal’s recognition of spiritual death. It continues with identifying the cause of this suffering as attachment and grasping. Daumal calls this “believing oneself to possess.” Buddhist renunciation (nekkhamma) resonates with the realization that “we have nothing,” and the practice of generous giving (dāna) reflects the attempt to give, which reveals our emptiness.

In the Christian mystical tradition, we find the same structure in Meister Eckhart’s teachings on absolute detachment and spiritual poverty. “As long as man still has within him the desire to fulfill God’s most cherished will, that man does not have the poverty we are talking about,” he writes. This indicates that even spiritual desire must be transcended to attain pure receptivity, where God can be born in the soul. This radical poverty corresponds to Daumal’s “seeing that one is nothing,” and the birth of God in the soul corresponds to the desire to become, which brings one into true life.

In Sufism, this progression is expressed through the stations (maqamat) and states (ahwal) of the spiritual path. It begins with conversion (tawba) and rejection of the material world (zuhd) and progresses toward the annihilation of the self (fana) and subsistence in God (baqa). “Seeing that one is nothing” corresponds to fana, the dissolution of the ego that precedes the emergence of the true being unified with the Real.

The convergence of the great spiritual traditions on this fundamental structure of the path—the recognition of the state of sleep or spiritual death, the dissolution of illusions and identifications, the death of the ego, and the rebirth of authentic being—confirms that Daumal is describing an experiential reality accessible to anyone who engages in the work of inner transformation, rather than inventing an abstract theory.

Implications for the contemporary spiritual quest

In today’s world, which is marked by a proliferation of often-superficial spiritual offerings, the commercialization of wisdom as a consumer product, and the confusion of psychological well-being with spiritual transformation, Daumal’s poem serves as a much-needed reminder of the demands and radicalism inherent in any authentic spiritual path. Our era loves easy promises, quick techniques, and spectacular experiences that don’t require us to question our way of life or our psychological makeup.

The personal development market offers thousands of methods to “improve” our lives, increase our performance, and optimize our well-being. But how many of these approaches truly address the question of being? How many invite us to recognize our spiritual death, our lack of essential qualities, and our emptiness in our ordinary state? Most contemporary approaches, on the contrary, reinforce the ego by promising more control, power, success, and happiness. Thus, they add additional layers of illusion rather than dissolving them.

Daumal’s poem reminds us that authentic spiritual transformation requires to go through the crisis of recognizing our true state and destroying illusions. This process may seem negative, but it is the necessary condition for reconstruction on solid foundations. The poem invites us to distinguish between having and being, possession and essence, and accumulation and transformation. He warns us against the pitfalls of spiritual possession, where we collect experiences, teachings, powers, and initiations without ever truly transforming ourselves.

He also emphasizes the importance of authentic desire and the aspiration to become, which can only emerge after false desires oriented toward possession are dissolved. This desire for transformation is a precious gift—a grace that cannot be commanded, but rather arises from the encounter between ruthless lucidity about our current state and the intuition that another way of being is possible. Cultivating this desire and protecting it from the countless distractions of contemporary life—giving it priority over all other desires—is a considerable spiritual task in itself.

Towards a concrete practice of awakening

How can we translate the teachings of this poem into concrete actions? How can we transition from an intellectual understanding to a lived application in our daily lives? Here are a few ideas inspired by Daumal’s text and the Gurdjieffian teachings from which it stems.

First, cultivate the ability to observe yourself without judgment or justification. Look at your internal mechanisms—thoughts, emotions, sensations, and reactions—with the same objectivity as a naturalist observing natural phenomena. This observation gradually reveals our lack of unity, our mechanical functioning, and our multiple identifications. Thus, it creates the conditions for the awareness Daumal speaks of.

Practice self-remembering in ordinary situations, which is the division of attention that allows us to be aware of what we are doing and the fact that we are doing it, the object and the subject, and the outside world and our inner presence simultaneously. This practice gradually develops continuous self-awareness, which constitutes the beginning of inner unity.

Regularly examine your possessions—material, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual—and ask yourself, “What do I believe I possess?” How do these possessions define my identity? What would happen if I lost them? This investigation reveals the identifications that keep us in a state of spiritual death and opens up the possibility of true detachment.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, engage in relationships with others with the intention of giving something essential—not to satisfy your ego or to feel useful, but as a genuine act of spiritual generosity. It is through this commitment to relationships that our limitations and illusions will be revealed and the authentic desire for transformation will emerge.

René Daumal’s poem does not offer easy consolation. Rather, it provides a rigorous map of the spiritual territory, tracing the path that leads from death to true life. We must follow it with courage and perseverance, knowing that “in desiring to become, we begin to live.”

© 2026 - The Dialogues of the New World by Jérôme Nathanaël

If you enjoy this publication, please help spread the word!

If you appreciate the approach of these Dialogues, please share them with others who might be interested!